|

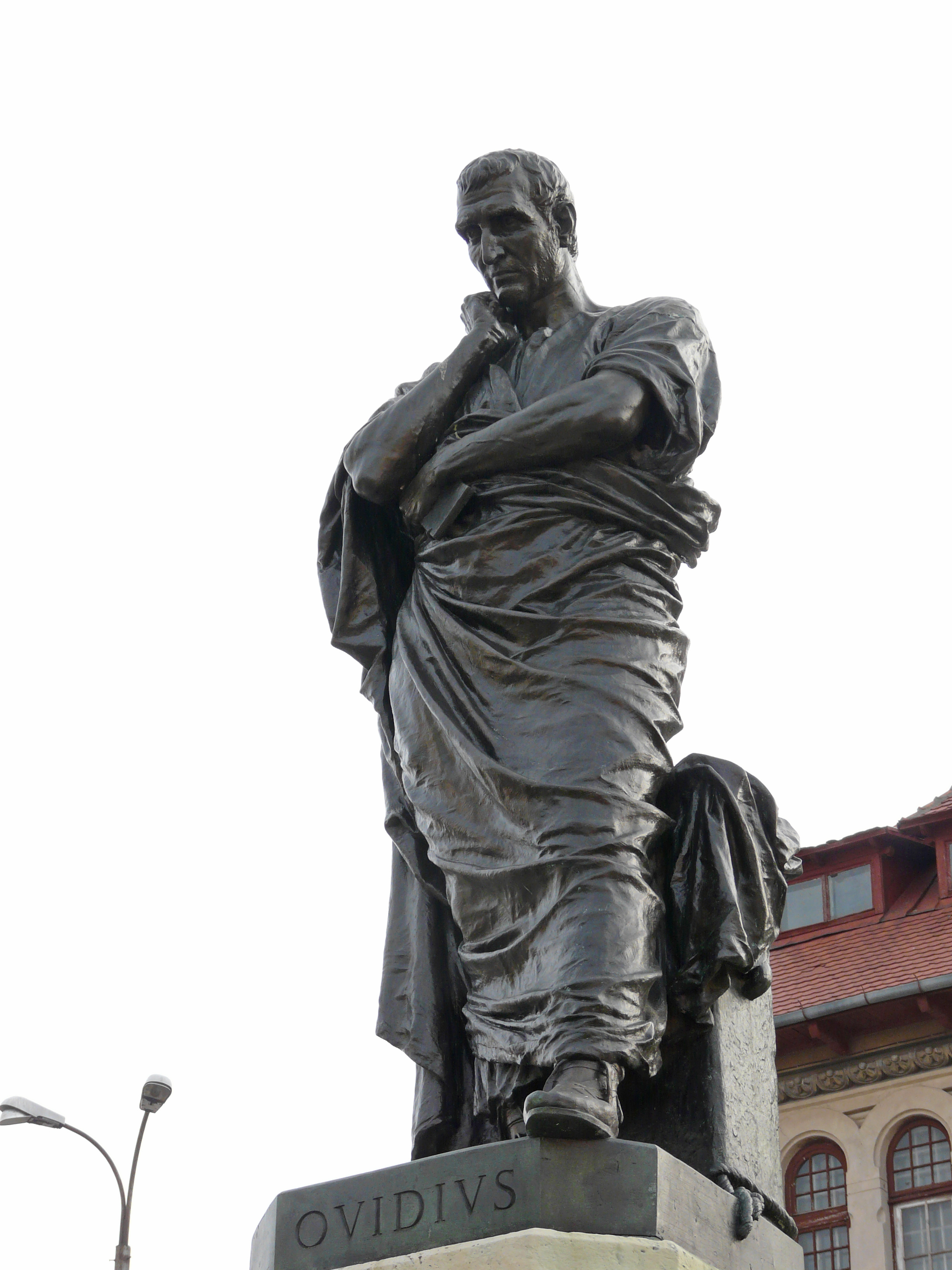

| Statue of Roman poet Ovid in Constanta. Image from WikiCommons. |

By Sal Buttaci

I have never felt comfortable

referring to myself as a poet. Instead, I tell folks I write poems. To me, the

designation “poet” is something I have always assigned to the master poets down

through Literature, those literary giants in whose works we still delight. Like most, I have quite a few poets whom I

consider favorites. I read their poems again and again and they never lose

their original appeal. The good feeling I get from reading about their lives

and their contributions to Literature never diminishes. In my own dry seasons

when I can’t seem to write a poem, those favorite poets of mine extend their

poems to me like oases to the thirsty.

I write poems. I study the craft of poetry writing. I taught

the craft of writing in middle schools, high schools, and colleges for many

years. On the average, I write close to a 1,000 poems a year. I’d write more,

but I also write fiction, so I try to balance the two as best I can. Still, to

my way of thinking, I am not a poet. I write poems.

If it were possible to count

the people in the world who write poetry, and may even profess to be poets, the

number might reach the total of our national debt. They are everywhere! Many

will confess, or even boast, they know nothing about poetry, but simply allow

their hearts to direct the pen or the fingers at the keyboard. I’ve heard some

brag that they never in their lives read more than the poems assigned in

school, let alone a how-to book on the poetry craft. The poems they write come

directly from their inner voices that insist on speaking out, mostly about love

and the absence of love. Some carry

business cards with “POET” under their names as if one day someone who holds

their card will find it necessary to phone them in a crisis and request a poem

be written the way one calls a plumber to repair a leaky faucet. Wanted: Poet.

Submit Resumé.

And the wage? Surely less than minimum, if at all!

I had a friend in Brooklyn

who wasn’t happy unless he threw Yiddish words and expressions into everything

he said. He got them from his grandmother, a Russian Jew who had immigrated to

America at the turn of the 20th Century. We were both in the fourth

grade at different schools. Nat went to P.S. 55 and I went to Most Holy Trinity

School, but we both lived in a predominantly Hasidic Jewish community

with only a smattering of the Irish and even fewer Italians.

Nat loved pulling pranks. I

tried to be the good angel on his shoulder, explaining why taking air out of

Mr. Finkle’s tires wasn’t very nice. Nat would wave his hand in the air and

say, “Finkle Shminkle! What do I care!” Or the time he walked backwards into

the Rainbow Theater at the same time the crowd was walking out, so he could

avoid paying the quarter admission and have money to buy popcorn and soda.

“Nat,” I said, horrified at

his deceit, “go back and pay the quarter. The Rainbow ain’t free!” Again, Nat

would wave his hand and say, “Rainbow Shmainbow, they got lots of quarters.

They don’t need mine!”

Who knows what became of my

old friend Nat. We moved away. I never even got the chance to tell my friends

since my father made the decision to move and the following day the Mayflower

van came and hauled our belongings to Flushing Avenue. I often imagine Nat

saying to himself or out loud to our circle of buddies, “Sal, Shmal, who needs

him!”

I know if I had just once

confided in him my new fascination with writing poems back then in 1950, he’d

laugh me off with “poet shmoet” and suggest we play stickball on Melrose Avenue

or walk to Johnson Ave. and check out the shop that sold used horror comics for

a nickel.

So in lieu of Nat, let me say

it instead. “Poet Shmoet!” Who needs a title to write poetry? Who needs

a label to feel validated? I am sure if

I were to ask my poetry heroes like Lorca and Vallejo, Cohen and Daly,

Shakespeare and Marlowe, Coleridge and Dante, Marinoni and Quasimodo, “How does

it feel to be a famous poet?” they would smile and say, “A poet? Hey, I just

write poems.”

#

|

| Add caption |

His recent flash collection, 200

Shorts, published by All Things That Matter Press, is available at http://www.amazon.com/200-Shorts-ebook/dp/B004YWKI8O/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1369920397&sr=1-2&keywords=200+Shorts

England’s Chester University

added 200 Shorts to their Flash

Fiction Special Collection at Seaborne Library in 2011. http://www.chester.ac.uk/flash.magazine/bibliography%20%20

Buttaci lives with his wife

Sharon in West Virginia.

salvatorebuttaci@yahoo.com

Thanks, Siggy, for posting my blog here at your excellent site!

ReplyDeleteOh, I enjoyed this so much. I always enjoy when you throw in your childhood friends and experiences - you come from such a different background and it seems so colorful and immediate... I am right there seeing it through your eyes.

ReplyDeleteI agree with you in this article. I don't call myself a poet. I think that is only what someone else can legitimately call another. You do, however, write wonderful poems and that is what counts.

Thanks, Debi. I love to write and that means the world to me. Whether others call me a poet or not is so much less important.

ReplyDeleteThanks for reading my article.